Global Compliance: Navigating Digital and Electronic Signature Laws

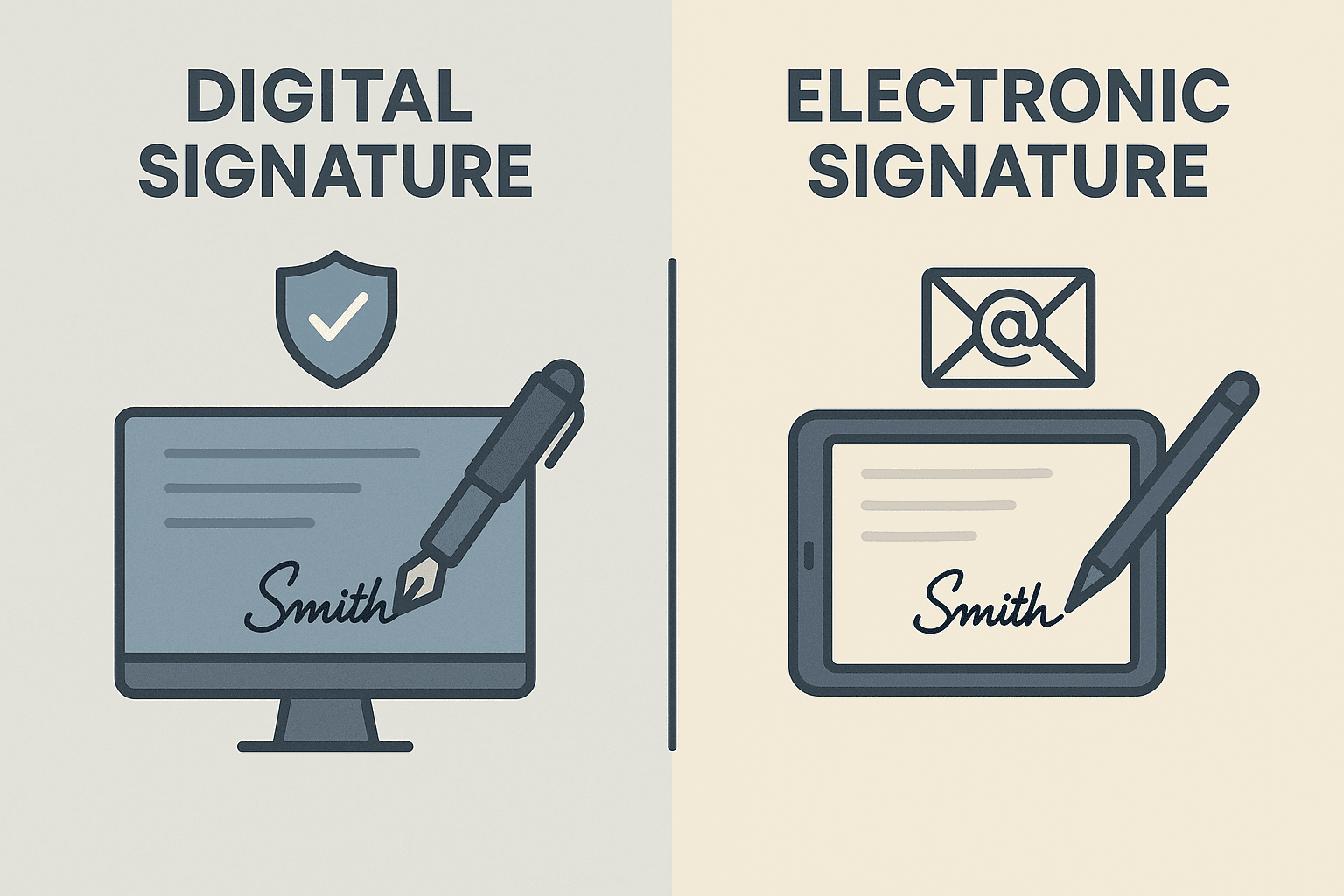

As digital transformation accelerates, electronic signatures have become a core technology for contract execution, document workflows, and transaction processing across industries. Yet many still conflate “electronic signature” and “digital signature,” assuming they are interchangeable—or overlooking their fundamental differences in technical implementation, security assurances, and legal compliance. In highly regulated sectors such as financial services, healthcare, manufacturing, and cross-border trade, choosing the right signing method affects not only compliance, but also downstream auditability and legal enforceability.

Technical Foundations: Different Mechanisms for Identity Assurance and Data Integrity

From a technology perspective, an electronic signature (e-signature) broadly refers to any electronic method of expressing a signer’s agreement to the contents of a document. It might be an inserted image, a click-to-accept button, or a captured handwritten stroke. Its core value lies in speed and ease of deployment, making it well-suited to low-to-moderate-risk processes. Across Asia, for example, many SMEs in Southeast Asia use such solutions for customer contracts and confirmation letters involving non-sensitive, lower-frequency documents—reducing manual effort and accelerating business turnaround.

A digital signature, by contrast, is a more rigorous cryptographic implementation. It is built on public key infrastructure (PKI), using asymmetric key pairs to generate a cryptographic signature and a digital certificate issued by a certificate authority (CA) to bind identity. Each signing action is traceable and tamper-evident, supporting non-repudiation. This is well-suited to high-sensitivity scenarios such as financial audit trails, corporate compliance documents, and cross-border trade agreements. In Mainland China, for example, digital signatures are embedded in regulatory requirements for financial services, e-government, and medical records—forming part of the compliance infrastructure.

Compliance and Legal Standing: Standards Encode Auditability and Accountability

Understanding the real fault line between the two requires a legal and regulatory lens. E-signatures are recognized across multiple jurisdictions—for instance, China’s Electronic Signature Law, Singapore’s Electronic Transactions Act (ETA), and the EU’s eIDAS Regulation. These frameworks generally accept e-signatures that demonstrate verifiability and clear intent as admissible evidence. However, enforceability often depends on context: how the signature is captured, the process controls around it, and the trust relationship between counterparties.

By comparison, certificate-based digital signatures typically map to “higher assurance” categories in statutory frameworks and carry greater legal weight. Under eIDAS, for example, a Qualified Electronic Signature (QES)—created with a qualified certificate and regulated signing device—enjoys legal equivalence to a handwritten signature. This is why organizations operating in EU capital markets or handling regulated data often prefer digital-signature-based solutions to minimize future legal disputes.

Real-World Use Cases: Risk Tiering Drives Technology Choices

In practice, digital and electronic signatures are not opposites; they serve different risk profiles. Consider a cross-border e-commerce platform: it might use e-signatures for user onboarding and service confirmations to maximize conversion, while relying on digital signatures for supplier agreements or contracts with overseas payment institutions to ensure cross-jurisdiction enforceability and clear compliance accountability.

A similar pattern is visible across Asian markets. In Hong Kong’s insurance sector, e-signatures are widely used for customer intent confirmations and online questionnaires. But filings to regulators and formal approvals typically require digital signatures with a full audit chain, ensuring the integrity and evidentiary readiness of records over time.

Security Considerations: The Core Control in a Risk-Mitigation Stack

While e-signatures are convenient, their security posture depends heavily on surrounding controls (e.g., authentication, session management). If an attacker gains access to the target system, signature forgery risks persist. Digital signatures, by design, bind a document’s hash to a private key; any alteration breaks verification. Consequently, against ransomware, insider tampering, or data exfiltration risks, enterprises often anchor their data-protection architecture on digital signatures.

As data sovereignty expectations rise—especially under China’s Data Security Law and Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL)—organizations face stricter requirements for auditability and accountability. Combined with trusted timestamps and certificate chains, digital signatures enable “sign-as-evidence” by default, materially reducing the burden of ex-post proof.

Operating for the Long Haul: Convergence of Electronic and Digital Signatures

Over the long term, digital signatures will not replace e-signatures, nor vice versa. Guided by policy and industry practice, more providers now offer multi-tier signature capabilities, allowing customers to switch methods based on document sensitivity, business risk, and regulatory thresholds.

For example, a large Korean conglomerate uses e-signatures across HR self-service flows—leave requests, onboarding/offboarding confirmations—while protecting employment contracts and compensation agreements with digital signatures. Integrated with enterprise identity systems such as LDAP, this approach balances security with operational efficiency.

Conclusion: Grasp the Essence to Make Resilient Technology Decisions

In practical terms, digital and electronic signatures represent two ends of a spectrum: assurance versus convenience. Deployment choices should be risk-based and adaptive—aligned to industry obligations, regulatory expectations, and data sensitivity. In Asia’s multi-jurisdiction environment, success in compliant digital transformation hinges on understanding where technology and law intersect, then operationalizing a tiered signature strategy accordingly.

Only business email allowed

Only business email allowed