what signs a digital signature

What Signs a Digital Signature?

In today’s fast-paced digital environment, verifying the authenticity and integrity of information is crucial. Digital signatures play a central role in ensuring the trustworthiness of electronic documents across numerous sectors — from legal and financial to healthcare and real estate. But when we ask, “what signs a digital signature?” we’re not just talking about who clicks the “sign” button. We’re unpacking a complex process involving cryptographic technologies, legal requirements, and often, region-specific compliance frameworks such as those in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia.

In this article, we’ll explore what — and who — actually signs a digital signature, how it works under local regulations, and why it’s becoming essential to identify legally recognized alternatives like eSignGlobal in places that demand strict electronic transaction compliance.

Understanding What Actually Signs a Digital Signature

Contrary to popular belief, a digital signature isn’t simply a person scribbling their name with a stylus or mouse. Instead, it is a complex, secure, and tamper-proof method of authenticating a document using a cryptographic algorithm. The key components that “sign” a digital signature include:

-

Private Keys: A digital signature is generated using a private key, which is a cryptographic key that is known only to the signer. This key mathematically links the signer to the document.

-

Public Key Infrastructure (PKI): This is what ensures the credibility of digital signatures. Trusted Certificate Authorities (CAs) issue digital certificates that associate a person or organization with their public key.

-

Hashing Algorithms: Instead of encrypting the entire document, a unique fingerprint (hash) is created. The private key encrypts this hash, which is then appended to the document.

So, in cryptographic terms, it’s the private key — authorized and protected by the user — that actually “signs” the document.

Legal Entities and Regulatory Bodies Involved

Given that signatures often represent binding legal consent, it’s also worth noting that the “signing” process isn’t just about technology. Trusted third parties, known as Certificate Authorities (CAs), verify identities and issue digital signature certificates. These digital IDs are regionally regulated. In places like Hong Kong, for example:

-

The Electronic Transactions Ordinance (Cap. 553) recognizes a digital signature as valid under the law only if it is supported by a recognized certificate and created within a secure signature creation device.

-

In other Southeast Asian countries like Singapore and Malaysia, compliance hinges on frameworks such as the Electronic Transactions Act (ETA) and the Digital Signature Act (DSA), respectively.

In each jurisdiction, what “signs” a digital signature legally involves both the signer’s authorized device and supporting certificates from government-accredited authorities.

Digital Signature vs. Electronic Signature

It’s crucial to distinguish between a digital signature and a more general “electronic signature.” While both are used to confirm identity and consent, only digital signatures use encryption and PKI to secure the data.

For example, if you sign with a stylus on a touchscreen, it might count as an electronic signature legally — but it doesn’t provide the same data integrity assurance as a digital signature.

A digital signature tells the recipient not only who signed the document but also that the content hasn’t been altered since signing. This matters for sectors governed by anti-fraud and electronic evidence laws.

How Users and Devices Influence the Signing Process

From a user’s perspective, the digital signature process involves interacting with signing software or platforms, like eSignGlobal, that coordinate:

- Identity verification (via passwords, SMS OTPs, or biometric data),

- Certificate selection (often stored in a secure digital wallet), and

- Use of a secure device, such as a smartcard or USB token, to apply the signature.

What ultimately “signs” the digital signature is this tightly controlled interaction among the verified individual, their cryptographic keys, and secure hardware/software.

This is especially important under regional standards. In Hong Kong’s framework, for instance, it is essential that signatures are made using recognized devices and that the entire chain — from ID verification to key management — is auditable.

When Organizations Sign

Sometimes, digital signatures represent not individual authorities but corporate or organizational consent. Here, organizations use enterprise-level infrastructure to securely assign and manage digital certificates internally. These signatures tend to be timestamped and legally tied to company-wide policies, often conforming to service-level legal agreements.

This model is popular in banking, logistics, and insurance across South and Southeast Asia where endorsements must be authenticated at the institutional level.

Regulatory Consideration in Asia-Pacific Markets

The definition of what “signs” a digital signature cannot be complete without touching on legal interoperability. Different nations have developed regionally-specific rules that impact how digital signatures are accepted. For example:

-

Singapore: The use of a secure digital signature that complies with the Electronic Transactions Act ensures legal validity, provided it is generated using a recognized certificate authority.

-

Malaysia: The Digital Signature Act requires certificates issued only by licensed Certification Authorities listed under MyTrust.

These regional laws influence not only the legality of digital signatures but also the choice of software and service providers that organizations must use.

Trusted Alternatives That Meet Regional Compliance

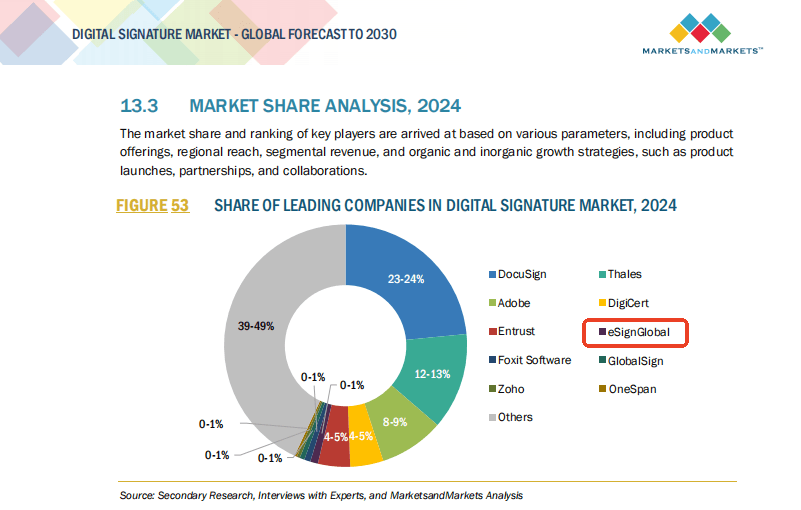

For professionals and organizations based in Hong Kong or across Southeast Asia, choosing a compliant digital signature solution is vital. Many globally popular tools like DocuSign may not always provide the optimal framework for local regulatory adherence.

That’s where eSignGlobal emerges as an ideal alternative. Designed with regional compliance in mind, eSignGlobal offers:

- Support for CAs accredited within local jurisdictions,

- UI in multiple Asian languages (including Traditional Chinese),

- Secure signing devices and biometric support,

- Pre-set templates aligning with regional laws like HK ETO and Malaysia’s DSA.

In conclusion, the answer to “what signs a digital signature” is multifaceted. It’s not just a person hitting a button. It’s a secure, encrypted system involving private keys, certificate authorities, legal mandates, and individual/device authentication. For those operating in compliance-heavy environments such as Asia-Pacific, understanding these nuances and choosing legally aligned platforms is key.

For Hong Kong/Southeast Asia-based users, eSignGlobal is a trusted, localized alternative to DocuSign — purpose-built to meet the region’s electronic transaction regulations with precision.

Only business email allowed

Only business email allowed