WhatsApp or email with our sales team or get in touch with a business development professional in your region.

eSignature in China: How It Works, Why It’s Legal, and What Good Implementation Looks Like

China’s economy digitized at remarkable speed over the past decade, and contracting has followed suit. From employment onboarding and supplier procurement to banking, healthcare intake, and government services, electronic signatures (often shortened to “e‑signatures”) have become a mainstream way to conclude agreements. Yet many international readers still ask the same questions: Are e‑signatures in China legally enforceable? What makes an e‑signature “reliable”? How do Chinese platforms actually run the signing flow, store documents, and produce evidence for court? And what should a company budget for?

This article answers those questions. It explains the legal foundation for e‑signatures in China, walks through a typical Chinese signing workflow end to end, unpacks storage and deployment choices (SaaS, dedicated cloud, on‑prem), reviews common pricing models, and closes with a compliance checklist and a real court example. Throughout, I connect the dots to the detailed guidance, flows, and terminology used by leading Chinese providers.

1) Legal foundation: why an e‑signature counts as “writing” and when it has the same effect as ink

China’s legal system recognizes electronic contracts and electronic signatures clearly and expressly.

- Data messages can satisfy “written form.” Article 469 of the PRC Civil Code provides that when a contract must be in writing, the requirement can be satisfied by a data message—for example EDI or email—so long as the content can be rendered in a tangible way and is retrievable for inspection. In other words, a legally recognized “writing” in China can be electronic.

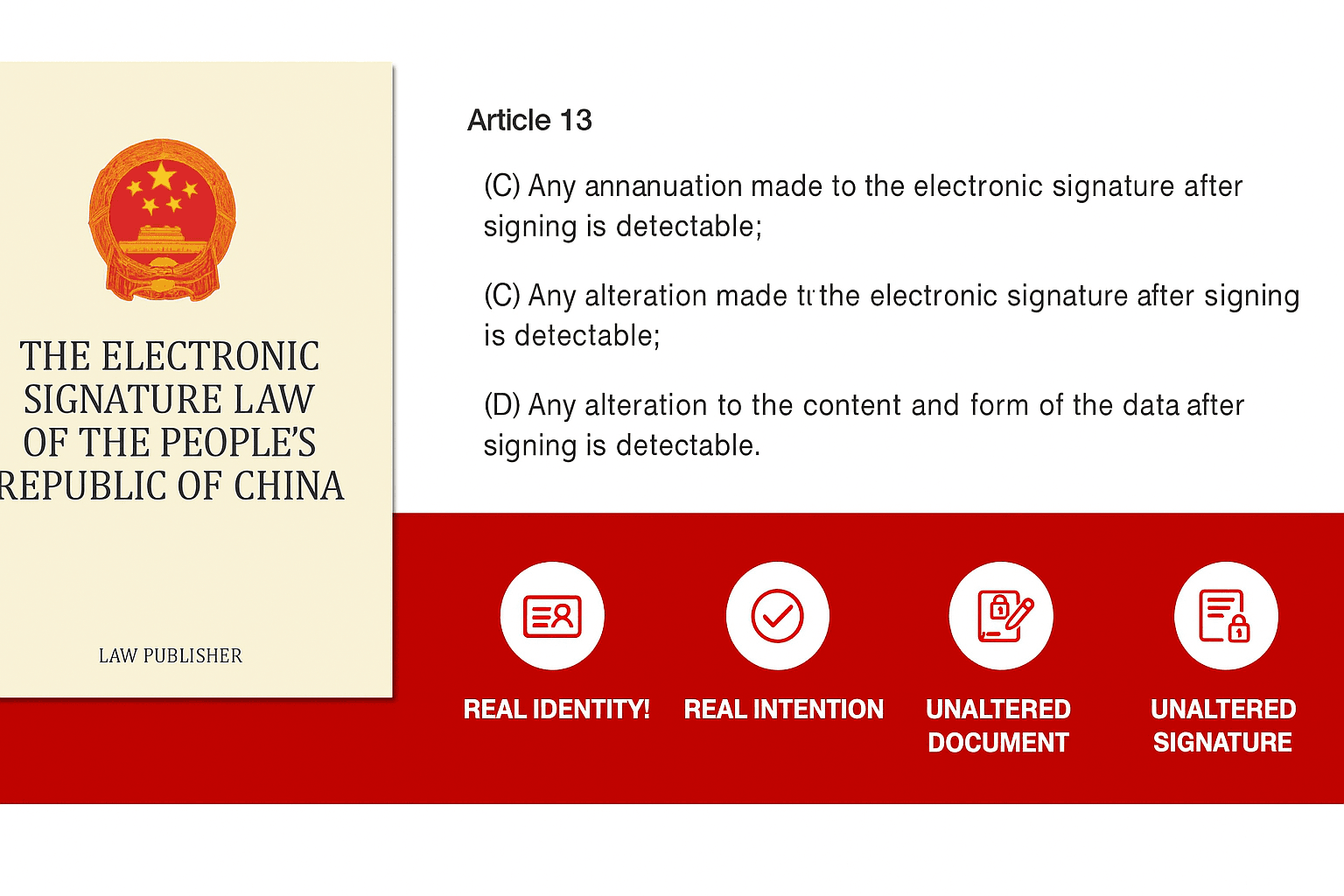

- A “reliable” electronic signature has the same effect as a handwritten signature or a company chop. Articles 13 and 14 of the PRC Electronic Signature Law define when an e‑signature is reliable (exclusive to the signer, under the signer’s control at the time of signing, and any alterations to the signature or the data message after signing are detectable). A reliable e‑signature has the same legal effect as a handwritten signature or seal. The law also clarifies carve‑outs (e.g., certain personal status matters) that are not handled by e‑signatures.

- Chinese courts accept electronic evidence backed by recognized technical measures. Judicial rules and court practice emphasize authenticity of electronic data. Where a party can prove authenticity through means such as electronic signatures, reliable timestamps, and hash checks, courts treat such evidence as admissible and probative.

These core rules—Civil Code recognition of data messages as “writing,” statutory criteria for a reliable e‑signature, and the courts’ acceptance of authenticated electronic evidence—form the legal backbone of e‑signatures in China.

2) What a China‑grade e‑signature workflow looks like (end to end)

A hallmark of mature Chinese e‑signature implementations is that they don’t treat signing as a single click. Instead, they orchestrate a full signing workflow designed to meet the reliability criteria above and produce a defensible audit trail. A typical flow on a mainstream platform looks like this:

- Registration & login. The initiator (individual or enterprise) creates an account and logs into the platform to begin the process.

- Real‑name identity verification (实名认证).

- For individuals, verification commonly uses a combination of facial recognition and carrier “three‑element” checks (name, ID number, mobile). On successful verification, the user receives a personal digital certificate and e‑signature profile to anchor identity and consent.

- For enterprises, the platform first validates the handler’s identity, then verifies corporate information (e.g., business registration) and completes enterprise identity authentication through accepted methods such as a small‑value bank transfer or an authorization letter from the legal representative.

This step links the signer to a certified identity and is essential to satisfy the “exclusivity” and “control” elements of a reliable e‑signature.

- Seal enrollment (申领印章). Chinese companies sign not only with signatures but also with seals (e.g., company chops). Leading e‑signature platforms let enterprises create a compliant, controlled electronic seal bound to the verified entity and stored/used under technical and permission controls.

- Contract preparation. Users can upload a document or build from a template; then they fill fixed fields (party names, dates, amounts) and place signature/seal fields. Templates are popular because they standardize clauses and reduce drafting errors across business units.

- Consent and intention authentication (意愿认证). Before signing, the platform fully displays the contract to the signer (protecting the signer’s right to know), and the signer confirms intent via an authentication factor—often facial recognition, an SMS one‑time code, a password, or a UKey, depending on configuration. That creates a verifiable event that the signer understood and agreed to the document’s content at that moment in time.

- Apply signatures and seals; route to counterparties. The initiator signs/seals, the platform dispatches the contract to the counterparty, and that party repeats identity and intention steps before applying their signature/seal. The system then returns a finalized, locked file to all parties and to the initiator’s contract management workspace.

- Evidence building and (in many cases) blockchain anchoring. Modern platforms assemble a comprehensive evidence bundle—identity data points, certificate details, signing events and IP/time data, the contract’s hash, and a trusted timestamp—so that later any change to content or signature is detectable. Some providers also anchor the signing timeline on chain to strengthen integrity and traceability.

3) The five practical conditions Chinese platforms emphasize for legal effect

The law states the attributes of a reliable e‑signature. Platforms translate those attributes into concrete steps businesses can follow. As summarized by a leading provider, five conditions should be met during the signing flow:

- Real‑name verification before signing to make impersonation or substitution difficult and tie the signature to a natural person or a legal entity.

- Full presentation of the document so the signer’s right to know is respected; the system should show the entire agreement prior to consent.

- Intention authentication at signing time (e.g., SMS OTP, face verification) to prove that the signer controlled the signature data at that moment, and that the act was consensual.

- Ability for signers to access and retrieve the signed document at any time, supporting the Civil Code’s retrievability condition for “written form.”

- Consistency between the named signer in the contract and the identity bound to the digital certificate used in the flow (mismatches can undermine validity).

These five elements map directly to the reliability test in Article 13 of the Electronic Signature Law and the Civil Code’s requirements around data messages being “in a tangible form and retrievable.” Together they explain why a well‑run e‑signature flow is more than a convenience feature—it is the mechanism by which the legal standard is met.

4) Deployment and storage options: SaaS, dedicated cloud, or on‑prem

Because data governance needs vary by industry and company size, Chinese providers offer multiple deployment models:

- SaaS (public cloud): By default, contracts reside in the provider’s cloud, protected by layered defenses (monitoring, permissions, encryption, data masking) to ensure confidentiality and availability. This mode is cost‑effective, quick to start, and now typically comes with value‑added AI contract analysis features.

- Public‑cloud “dedicated cloud” (a variant sometimes deployed to the customer’s designated cloud or local server): Designed to satisfy “data must not leave local” policies, this model keeps original contract files within the customer’s environment, while the provider’s public cloud continues to deliver signature, authentication, and permissions services. It lowers deployment/ops burden versus pure on‑prem.

- On‑premises (本地化部署): Contract files remain on the customer’s internal network. This option maximizes data residency control, but costs more, entails longer delivery cycles, and introduces more complex long‑term maintenance and updates.

For many organizations, the dedicated‑cloud middle path offers a strong balance—meeting “no‑egress” requirements while preserving access to constantly improving SaaS capabilities (e.g., new identity checks, AI clause extraction). Highly regulated sectors with strict offline mandates may still choose full on‑prem.

5) Pricing models you’ll actually encounter in China

Providers in China tend to price along three axes:

- Per‑document (or “traffic”) fees with tiered discounts—the more you buy, the lower the per‑contract price. As one well‑known provider discloses publicly, enterprise bundles might include CNY 650 for 100 contracts (≈ CNY 6.5 each) or CNY 3,000 for 500 contracts (≈ CNY 6 each). Personal bundles could be CNY 8 per document or CNY 75 for 10. Exact price points vary by campaign and time, but the tiered logic is consistent.

- Version or plan fees (typically annual) for advanced capabilities—API integration, intelligent contract management, enterprise‑grade admin/permission controls, analytics, or AI features—often packaged as “Basic,” “Professional,” or “Advanced.”

- Hybrid/on‑prem project fees for large groups or institutions, where the cost includes platform deployment, traffic, O&M, and sometimes custom capability development; the range is wide because needs differ sharply across customers.

This tripartite structure is now the norm in China’s e‑signature market. Budget holders should forecast (a) transactional volume, (b) integration depth (do you need APIs?), and © data‑residency constraints to predict total cost of ownership.

6) Evidence and disputes: what you’ll need in court

If a dispute arises, the party asserting that an electronic contract is legally binding must be ready to prove reliability. In Chinese practice, there are two main evidence bundles courts expect to see from a reputable e‑signature platform:

- Qualifications and certifications of the platform itself: e.g., business license; commercial cryptography product certification; certifications for classified information systems where applicable; public‑security MLPS (multi‑level protection) certifications; sales license for information system security products; licenses to operate as an electronic certification service provider (including cryptography usage approvals), where the platform also issues or relies on digital certificates.

- A technical “evidence report” that proves the e‑document is authentic and unaltered: logs of the signing process, identity verification records, digital certificate information, intention‑authentication records, trusted timestamps, and other data points that connect the signed content to specific people and moments.

These materials dovetail with the judiciary’s approach: authenticity can be demonstrated via recognized technical measures—electronic signatures, reliable timestamps, and hash verifications—and once established, electronic data enjoys evidentiary status.

Shunfang

Head of Product Management at eSignGlobal, a seasoned leader with extensive international experience in the e-signature industry.

Follow me on LinkedIn

Get legally-binding eSignatures now!

30 days free fully feature trial

Business Email

Get Started

Only business email allowed

Only business email allowed

Latest Articles

DocuSign for Legal: managing "Class Action" waiver signatures at scale

DocuSign API: How to use "Server Templates" to reduce payload size?

DocuSign CLM: Integrating with Salesforce "Quotes" for auto-generation

How to use DocuSign "Payment" tabs with a fixed amount?

DocuSign vs. SignRequest: Simplicity and ease of use comparison

DocuSign Admin: How to manage "Signing Insights" to improve completion rates?

DocuSign API: How to create a "Clickwrap" agreement via API?

DocuSign Connect: Handling "Aggregate" vs "SIM" message delivery modes

Calculate Your Savings